Many woodworkers have dust collection systems, which use suction and large pipes and hoses to collect sawdust and other particles from power tools. For the hobbyist, these systems can be affordable, below $1000 for a decent system. Naturally, I therefore wondered what I could accomplish with my old shop vacuum, some junk from the garbage can, and about 20 bucks.

Woodshop Dust Control Amazon IndieBound |

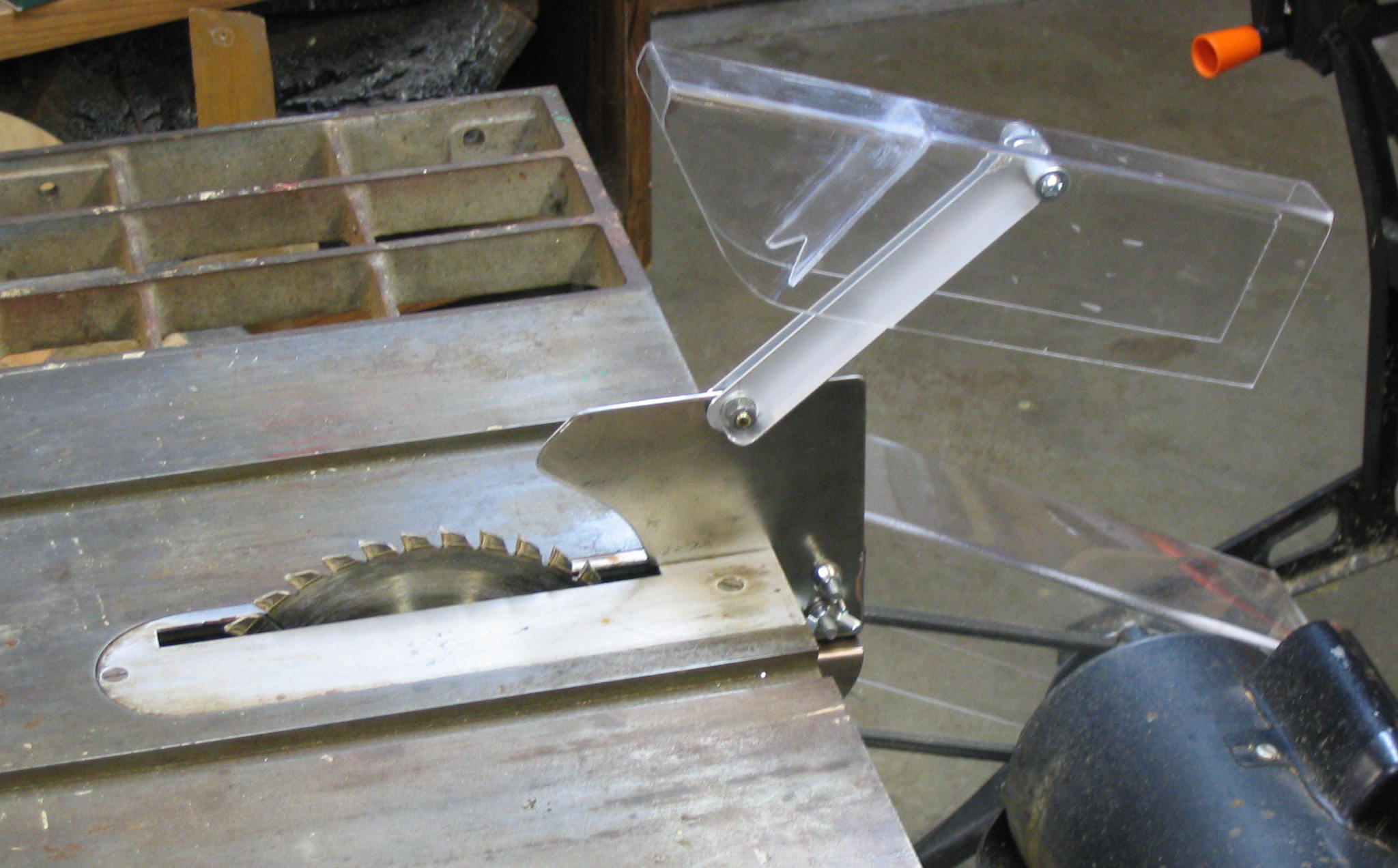

The basic premise is to collect sawdust, trimmings, and other particles as close to the source of production as possible. Many power tools come with dust collection ports built in to them these days. My 1950s PowrKraft table saw did not, so I set out to create a dust collector for it.

The Tablesaw

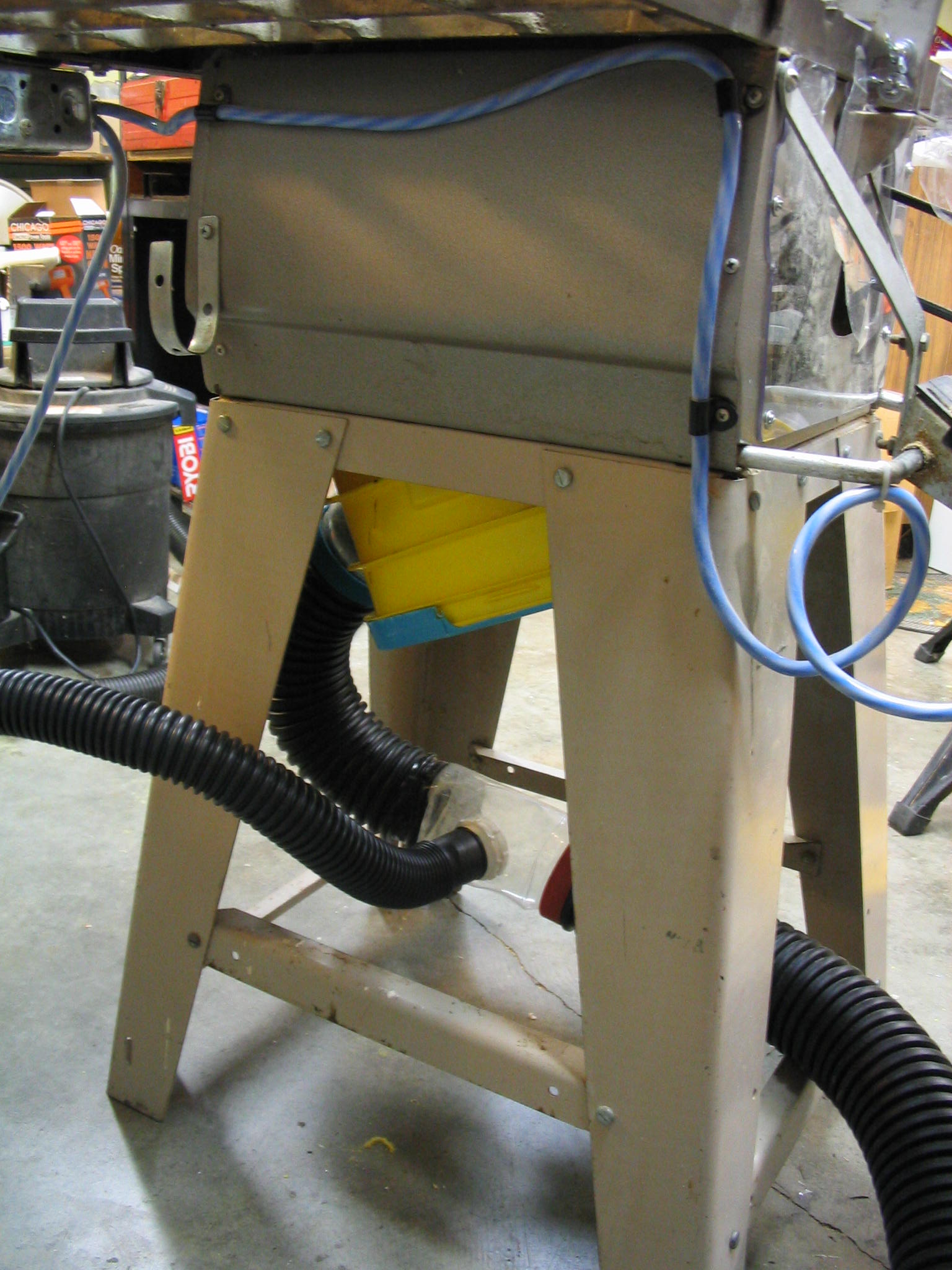

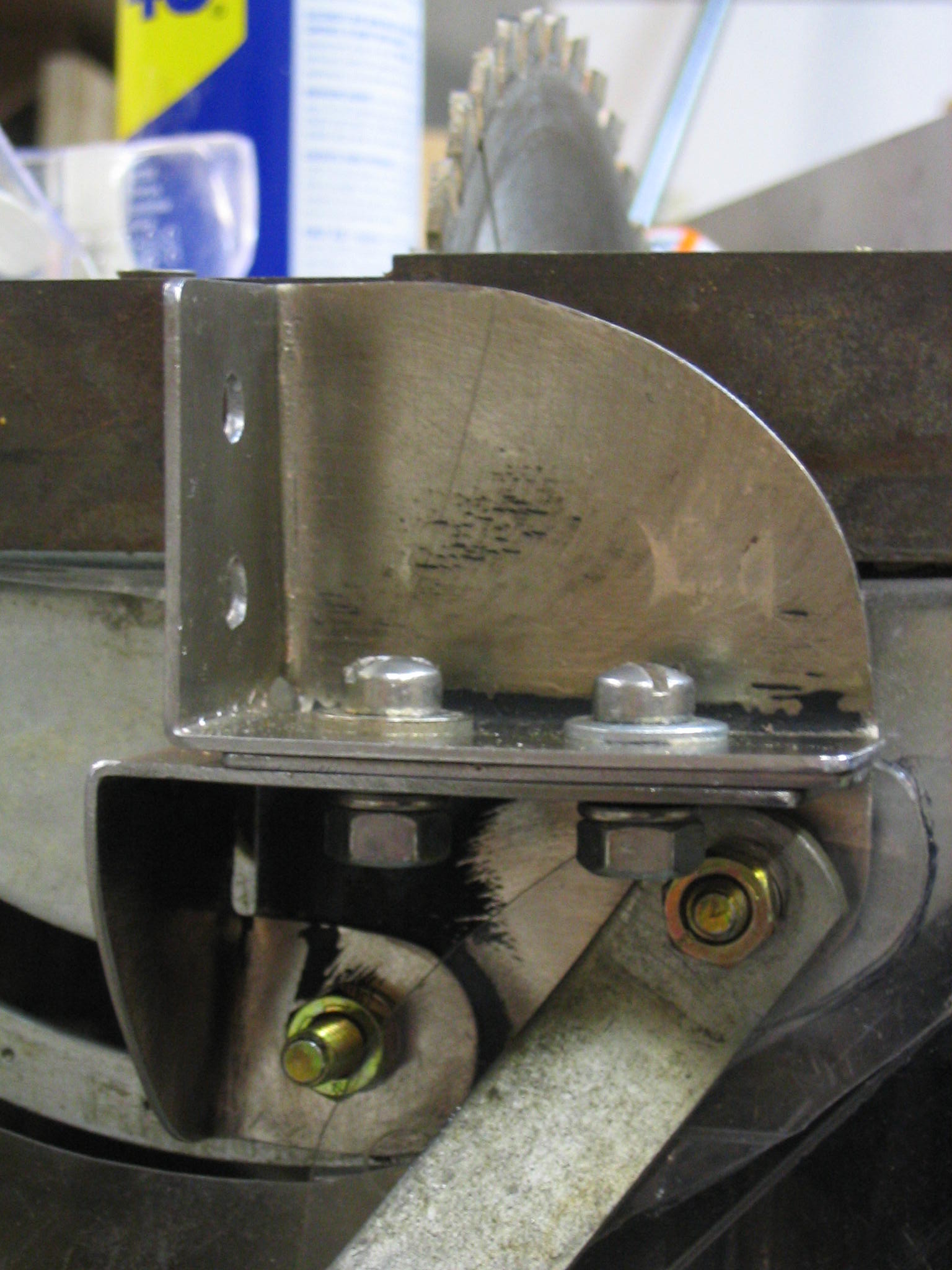

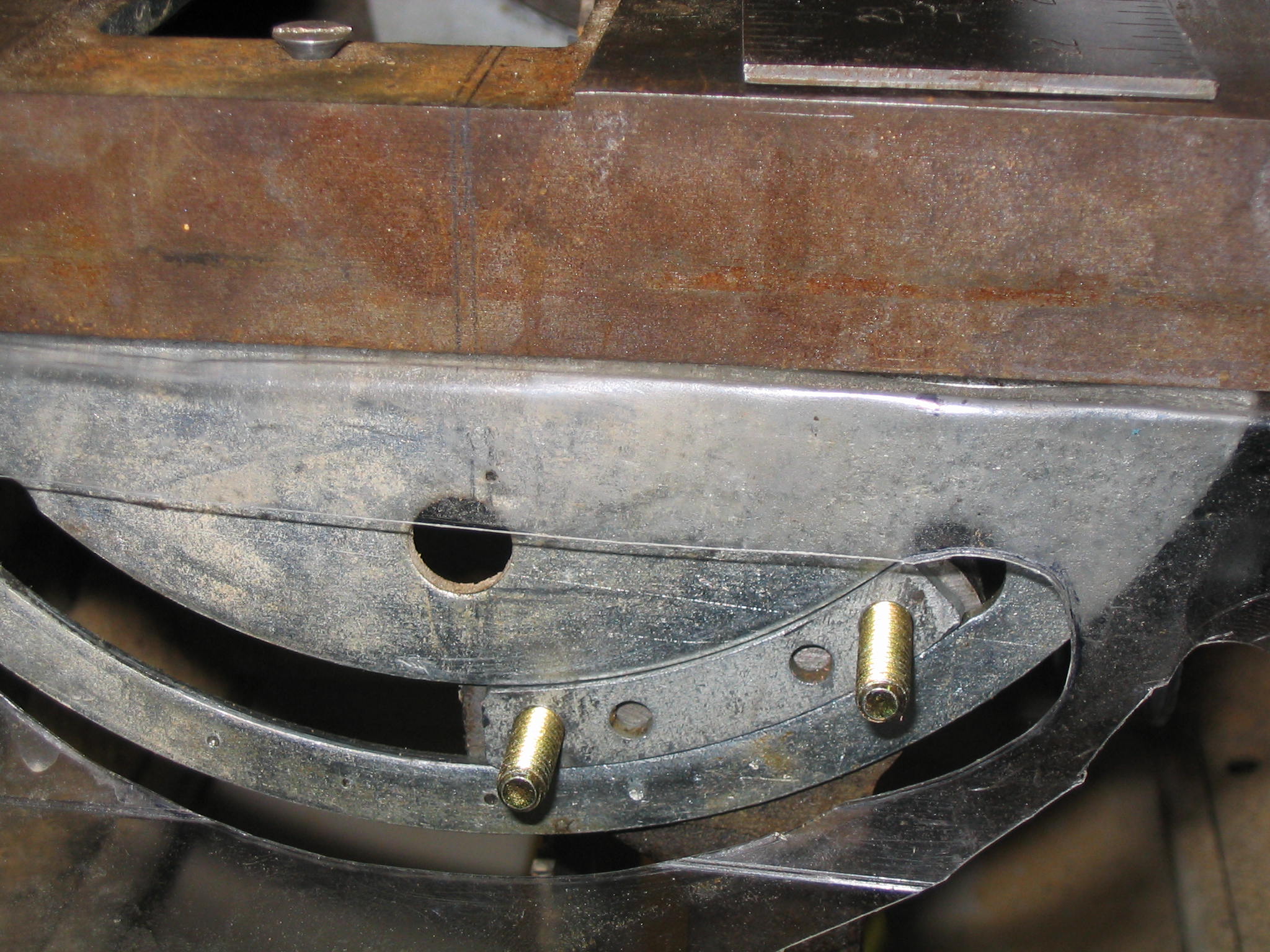

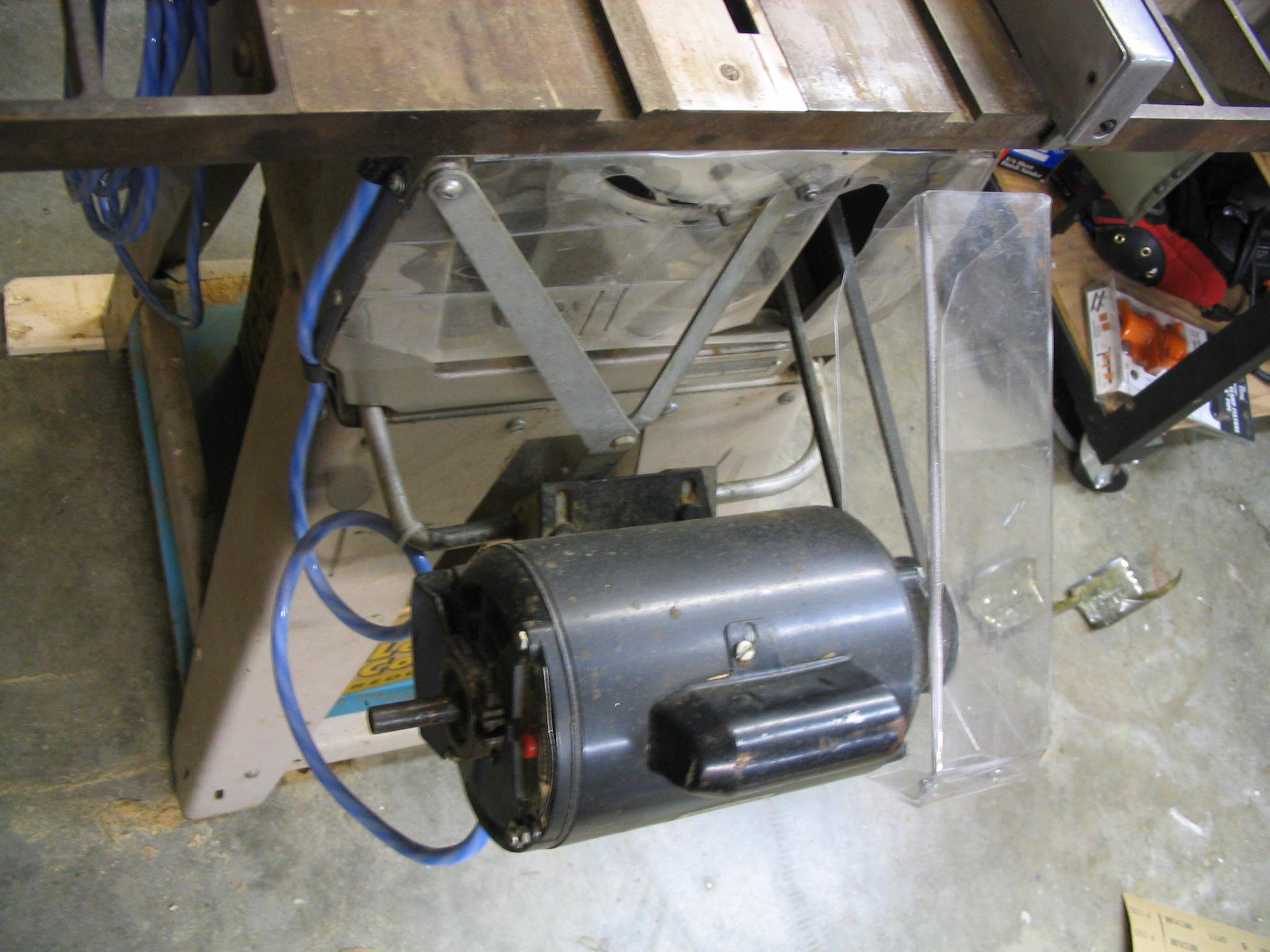

My tablesaw was not designed for vacuum collection of sawdust, so it has quite a few openings which needed to be covered. The underside of the saw is open, with a sheet-metal rim around the inside. This made a good place to attach a collection hood. I fabricated one from a rectangular plastic bucket made from HDPE (high-density polyethylene) plastic, the most common type used in common buckets and consumer packaging.

Since the bucket had a hinged snap-on lid, I turned the bucket upside down and used the lid as the bottom of the dust hood. The lid then became an access door to the underside of the saw. I used the heat gun to bend the sides of the bucket and weld on extra corner tabs, creating flanges to sit on the rim of the saw opening.

Tubing

For the dust-collection tubing, I took the cheap route. I used 3-inch water drainage tubing and 1.5-inch sump pump tubing, both from the local home improvement warehouse store.

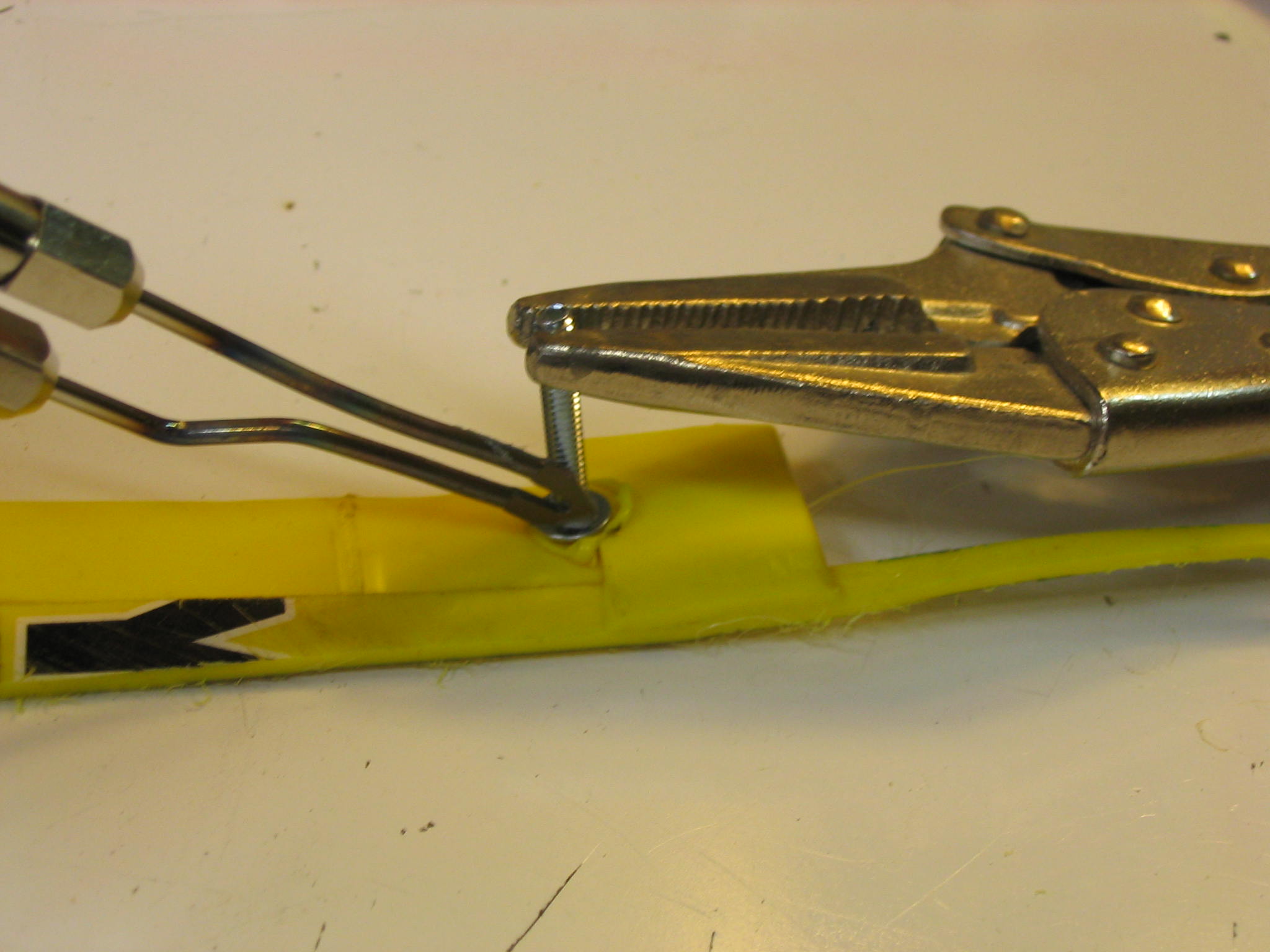

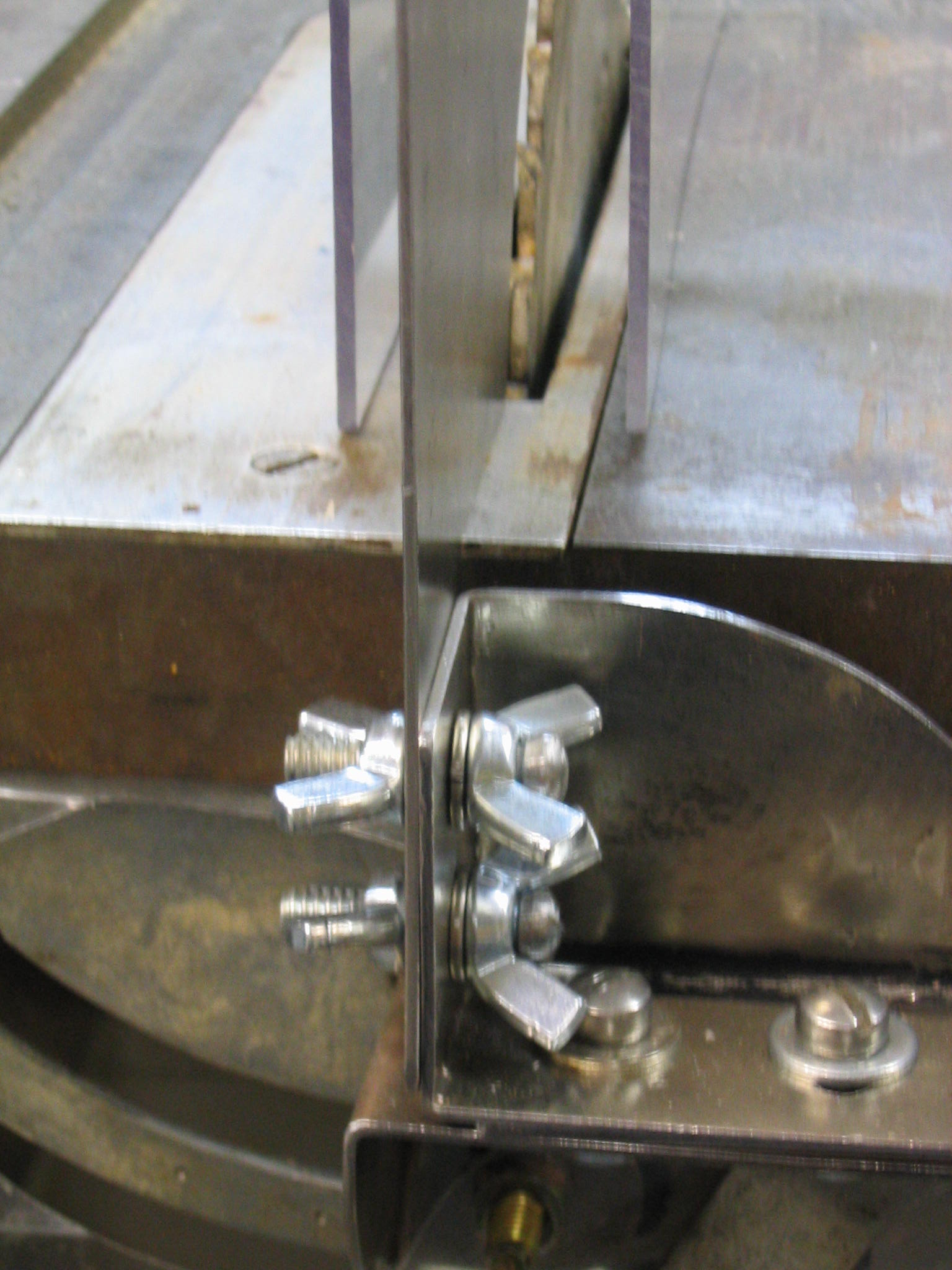

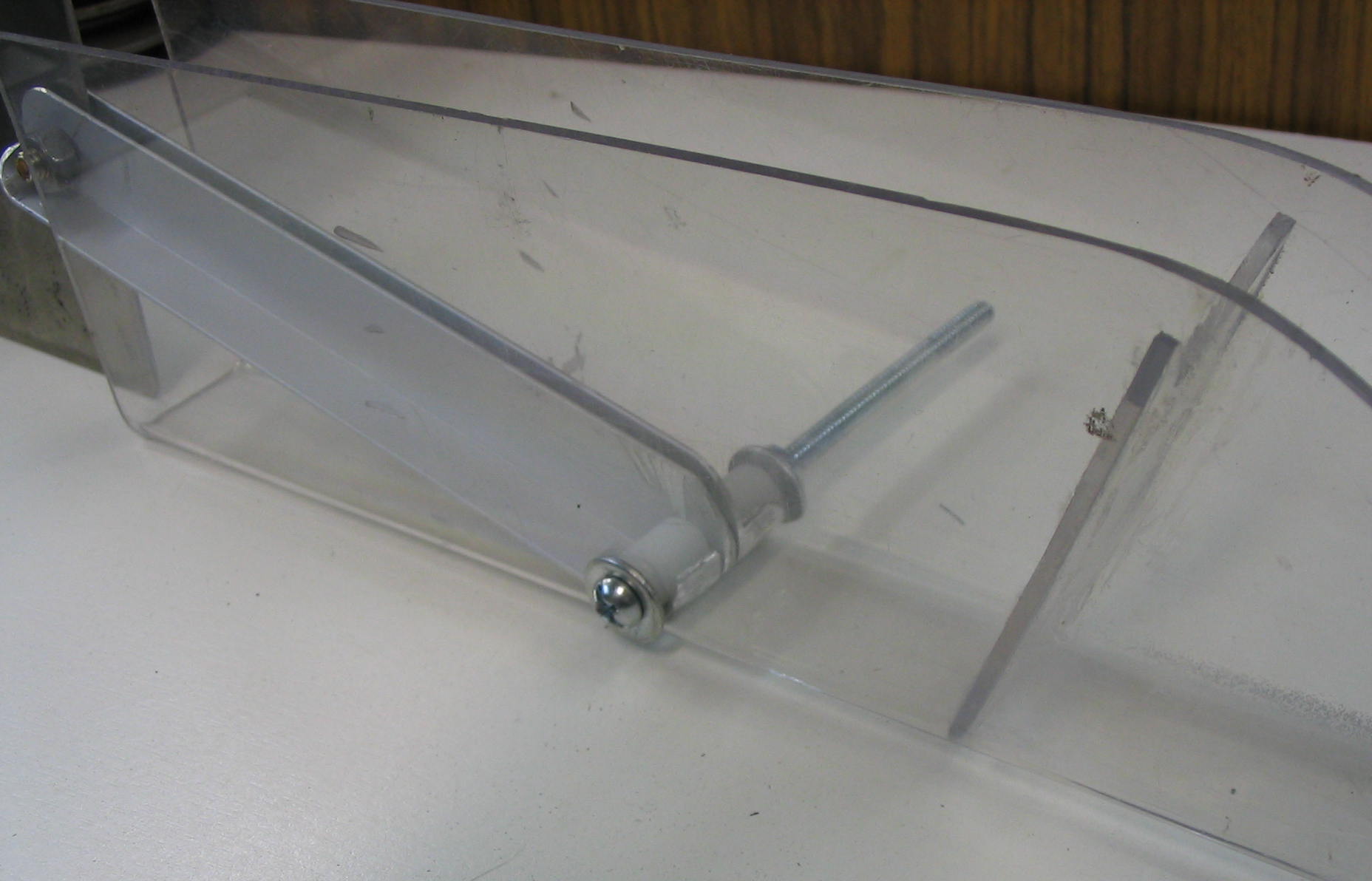

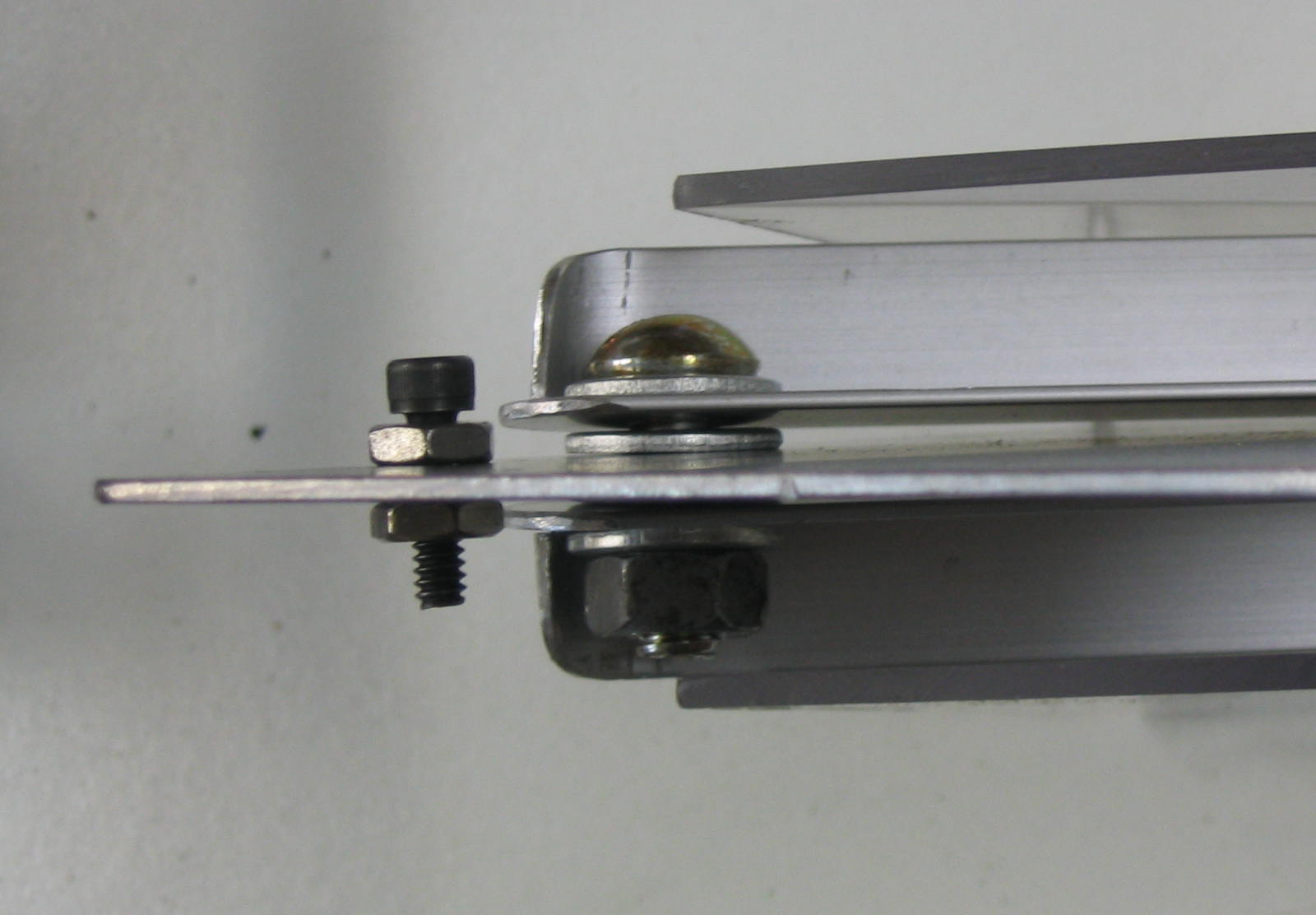

Neither one of the tubing sizes I used matches the hose of my shop vac at 2.5 inches, so I needed some adaptors. Several different plastic jars from peanut butter and applesauce turned out to be very close to the correct size. The opening on the applesauce jar was just a little too small, so I made a spreader jig with some wooden wedges between some nuts and washers. When one of the nuts is tightened, the washers squeeze the wedges, forcing them outward. I wrapped the wooden wedges in a piece of sheet metal from a tin vegetable can, and placed the mouth of the jar over it. By softening the jar mouth with the heat gun, and tightening the nut, I was able to expand the jar to fit the vacuum hose just right. I attached the 3-inch tubing to a hole I cut in the bottom of the jar on the other end, making a nice hose adaptor.

What’s That Noise?!

I put two dust collection points into the tablesaw collector: the large main 3-inch hose in the collector hood, and a second 1.5-inch hose to pick up stray sawdust from the top of the table. I attached them together with a Y-connection made from a plastic peanut butter jar. The 1.5-inch hose came out of the side of the jar, but I heated and warped the jar to make a Y connector for better airflow through the smaller hose.

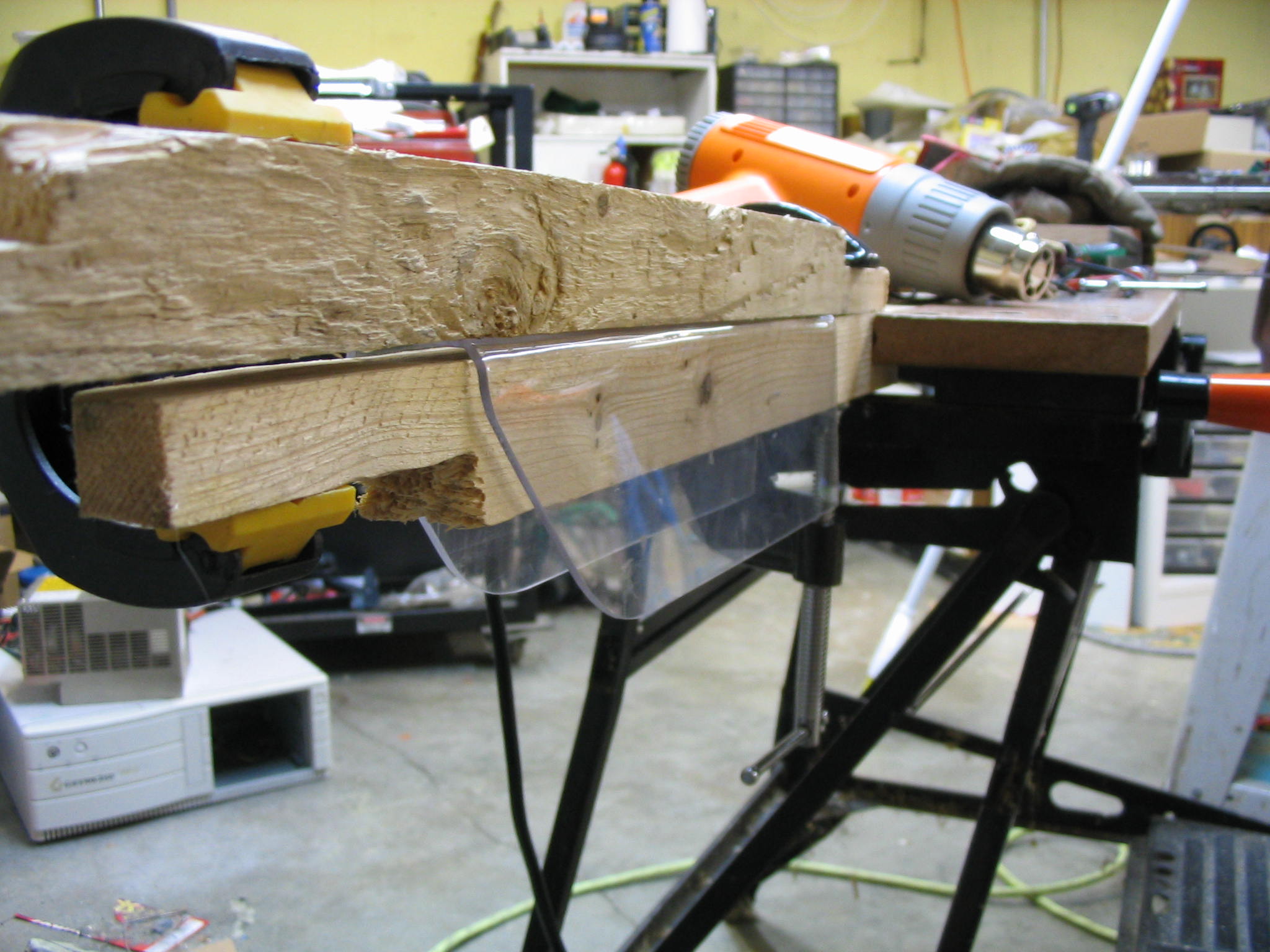

The first time I turned on the shop vacuum with this setup, I got a big surprise. In addition to the usual loud shop vac whine, I got an additional loud piercing whistle noise from the 1.5-inch hose. Some Internet research told me this was a “standing wave” harmonic vibration, caused by the uniform ridges in the hose. The factory did an accurate job of creating all of the ridges in the hose the same. When air passes through the hose, the ridges cause the air to vibrate at the same frequency all along the hose, causing a single tone to come out. It’s one big whistle.

Ironically, my web search efforts revealed much about how to produce such a noise, but not how to surpress it. However, some thought and experimentation led to a simple answer: If the uniform ridges make the whistling noise, making them non-uniform should eliminate it. I heated the hose with the heat gun, and stretched it by different amounts at different points along the hose. It didn’t take much stretching to disrupt the harmonic effect, eliminating the shriek and producing quieter air flow.

Particle Separator

I use the tablesaw to cut both wood and plastic at different times. I want to keep the two separated so the wood sawdust can be used for composting, without being contaminated by plastic pieces.

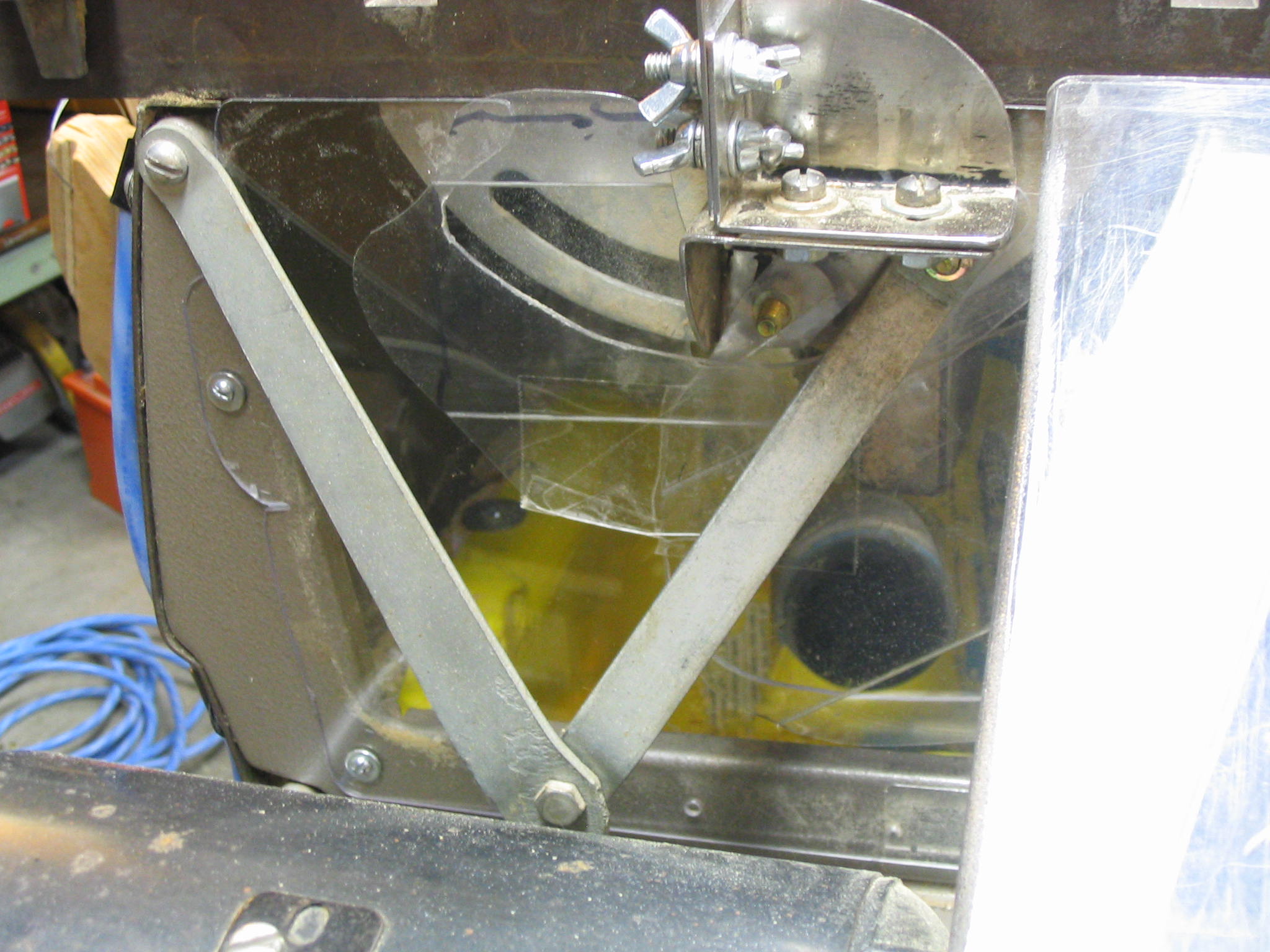

I made a pre-separator to collect the wood sawdust using a 5-gallon paint bucket. The separator bucket sits between the tablesaw and the shop vac. Scraps and larger sawdust particles settle to the bottom of the bucket, while the air and fine dust pass through to the vacuum. It is patterened after professional cyclone separators, where the incoming airflow is directed towards the side of the cylinder and the air exit is in the center. As the particles are blown towards the sides, they lose velocity and swirl down to the bottom.

There are just a few parts to the separator. The vacuum port (air exit) has a tube going down the center of the cylinder, which I made from a clear plastic applesauce jar with a mouth sized to the 2.5-inch vacuum hose, screwed into the bucket lid . The intake port goes to a deflector which sends the air towards the inside wall of the bucket. The intake port is a snap-on connector for the drain tubing, and the deflector is a scrap of plastic. Since the tube connector, deflector, and bucket lid are all HDPE plastic, I welded them together with the heat gun. I also cut a window into the side of the bucket, to indicate how full it is.

Now when I cut wood, I plug the vacuum in to the separator, and my wood cuttings are collected in the bucket. If I want to cut plastic, I bypass the separator and suck the plastic scraps right into the shop vac.

Airborne dust filter

To reduce airborne free-floating dust, I employed a trick which I saw recently in a home improvement magazine. I took a normal household box fan, and attached a furnace filter onto the intake side of the fan. I took the plastic grill off the intake side of the fan and reattached it with spacers and longer screws, allowing me to simply slide the furnace filter into the slot. It works quite effectively, producing a nice brown circle on the filter in no time at all. This is good, showing dust that is not getting inhaled or settling on everything else.

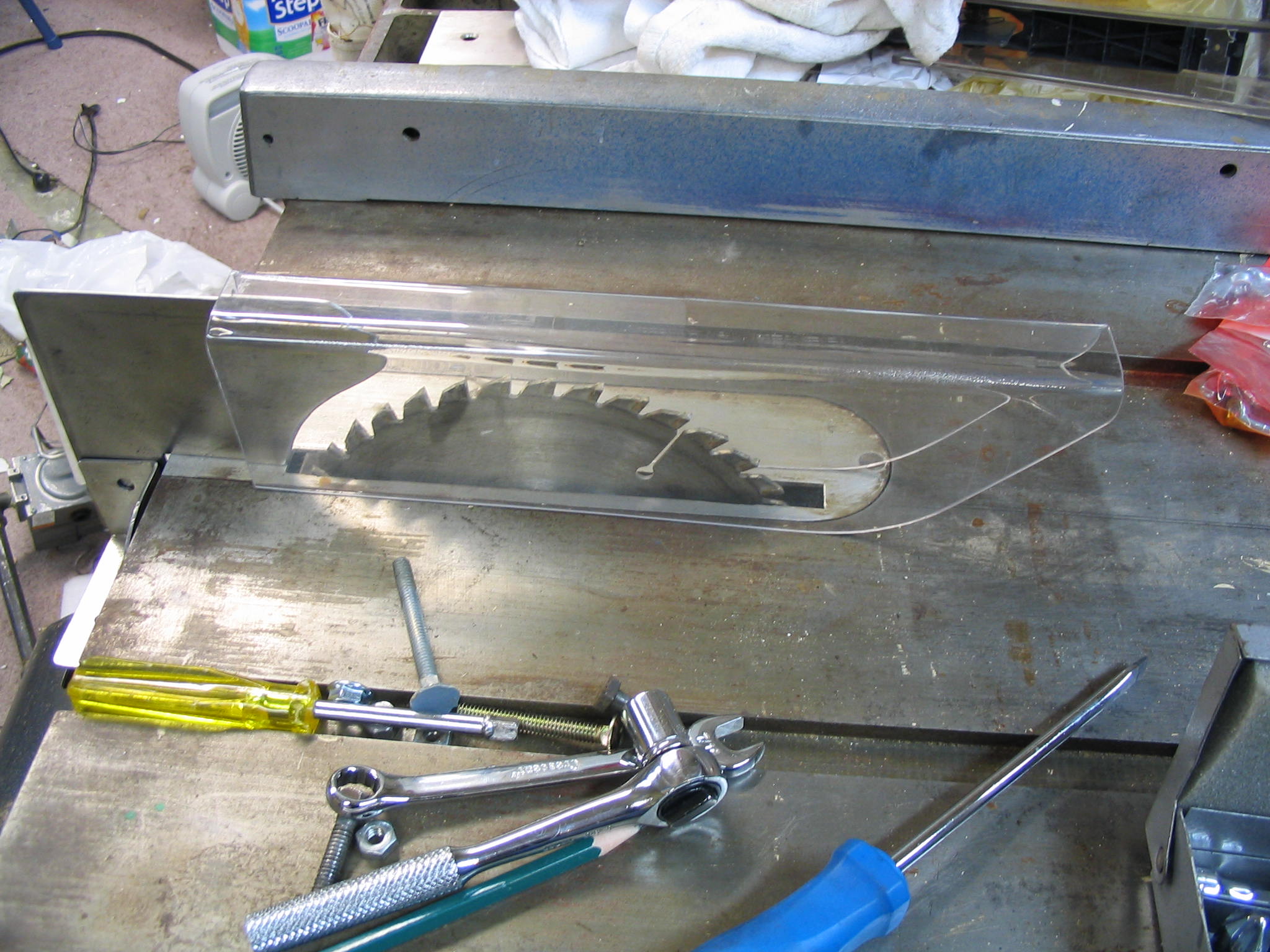

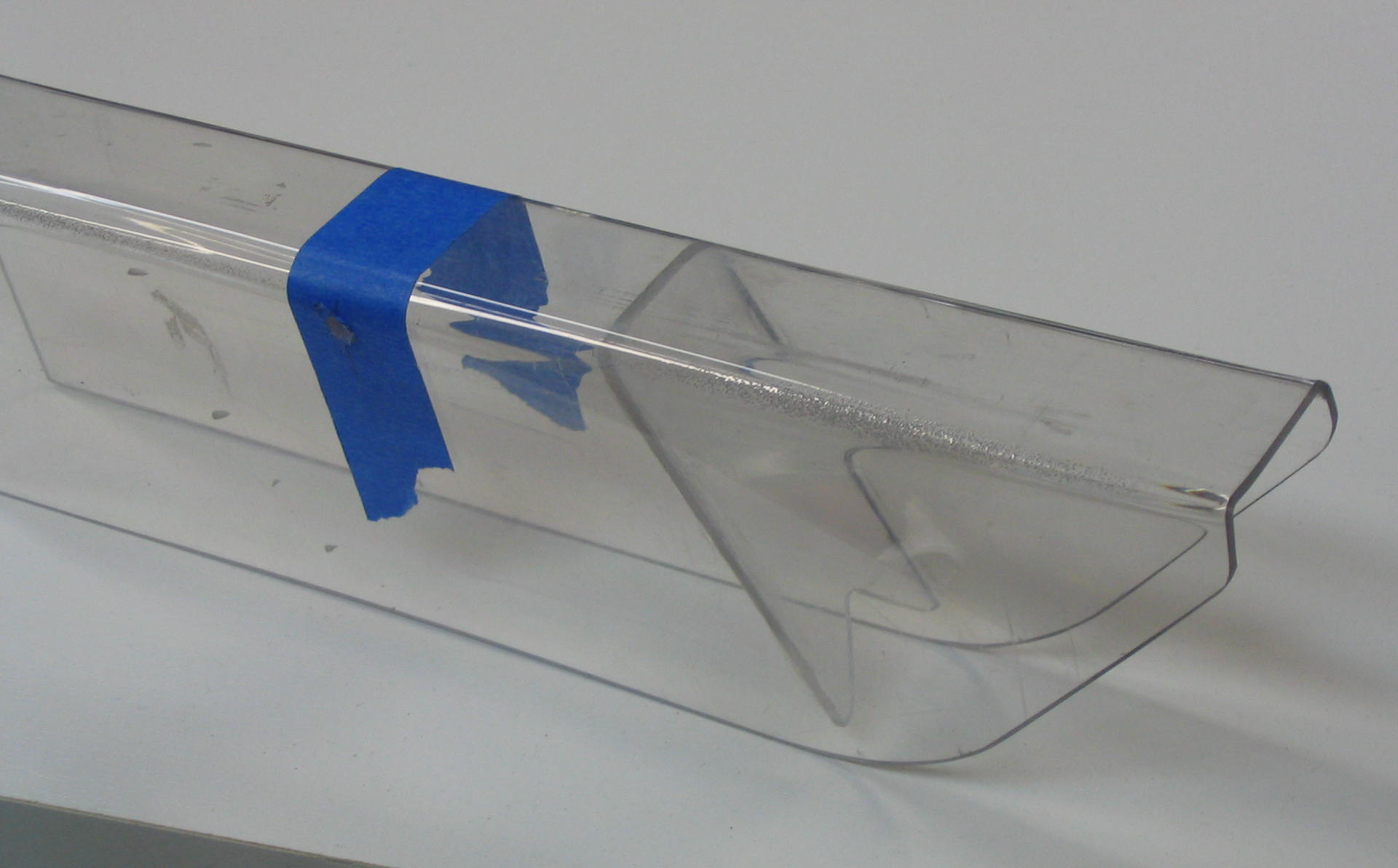

I set out to create a dust collection hood for the underside of my tablesaw. I used the top section of a rectangular HDPE plastic bucket with a snap-on hinged lid. Using an angled cross-section gave me a built-in slope for dust collection at the bottom. The lid of the bucket provides an access door to the underside of the saw, for reaching in to change the belt.

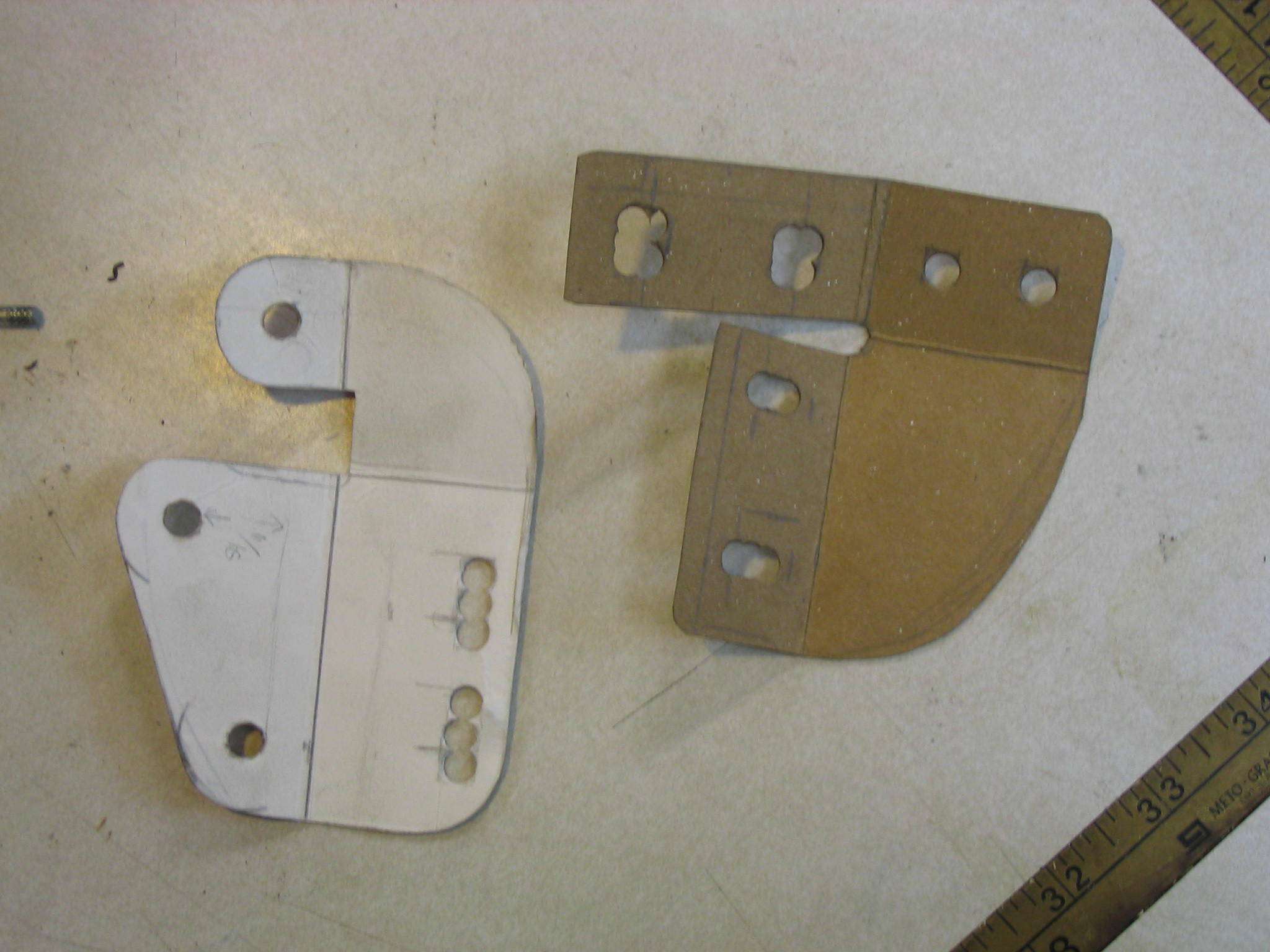

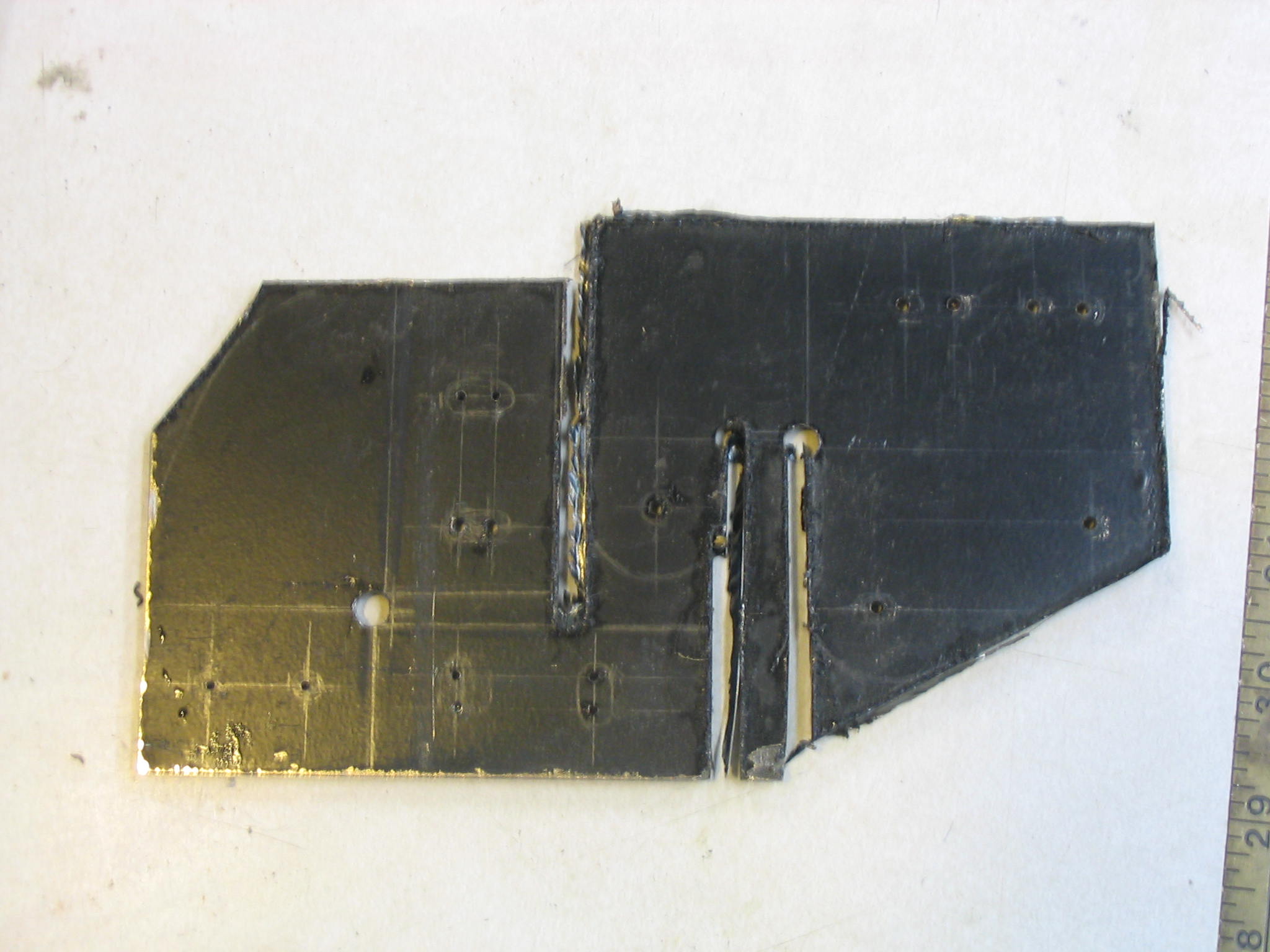

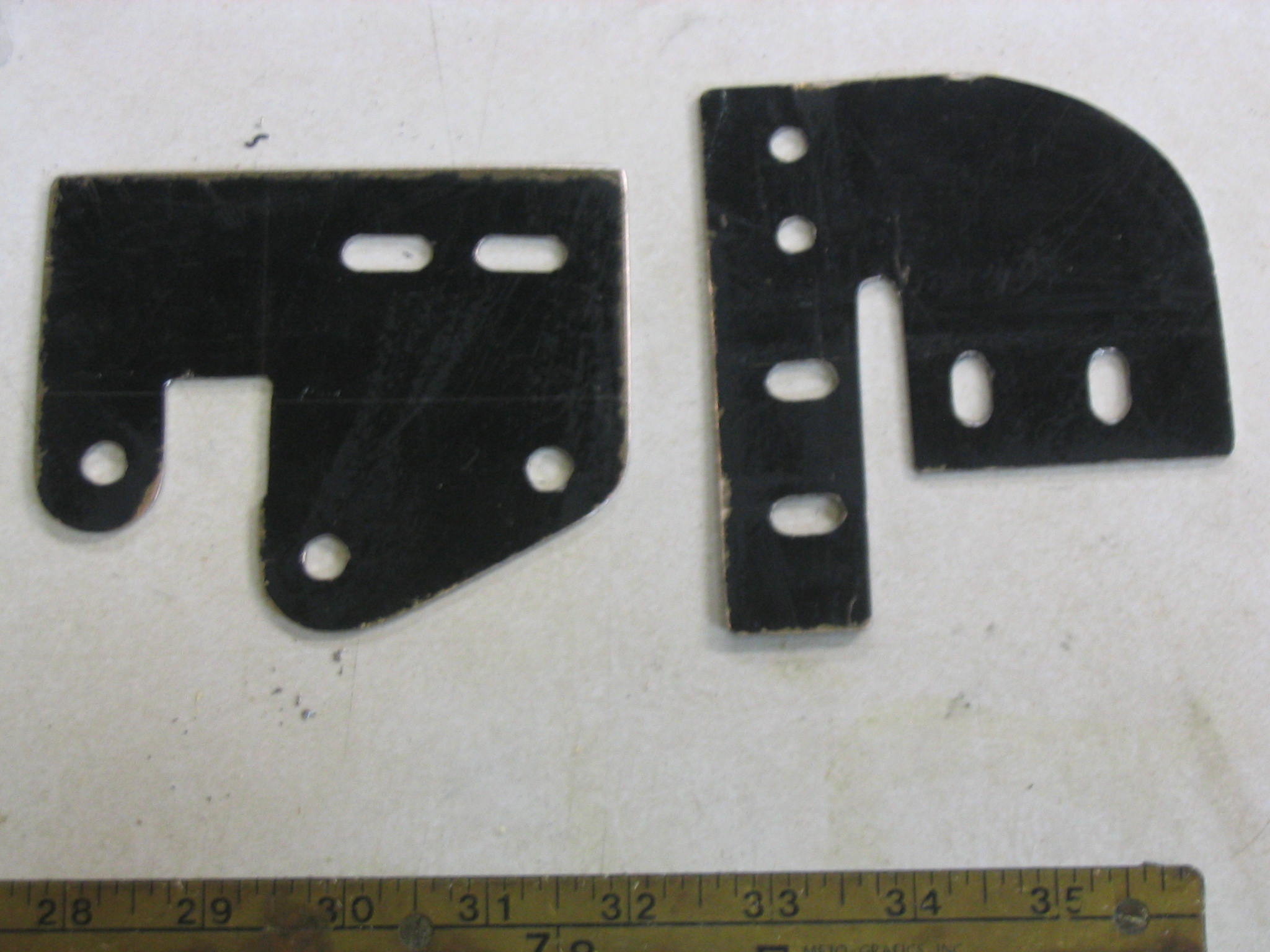

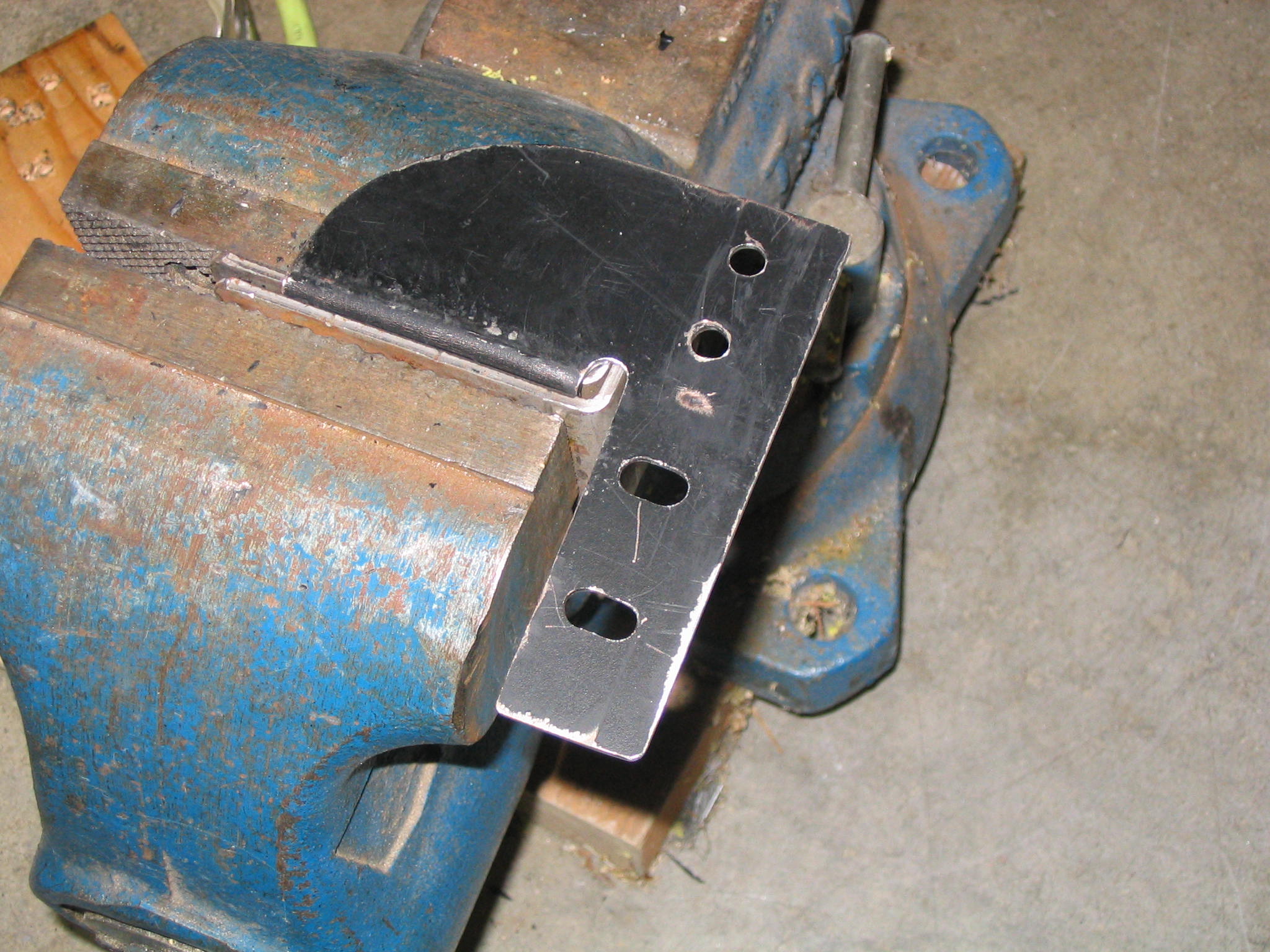

I set out to create a dust collection hood for the underside of my tablesaw. I used the top section of a rectangular HDPE plastic bucket with a snap-on hinged lid. Using an angled cross-section gave me a built-in slope for dust collection at the bottom. The lid of the bucket provides an access door to the underside of the saw, for reaching in to change the belt. I heated and bent the sides to create the main part of the rim. I slit the curved corner sections to make tabs. Then I added flat corner pieces and welded them to the tabs.

I heated and bent the sides to create the main part of the rim. I slit the curved corner sections to make tabs. Then I added flat corner pieces and welded them to the tabs. The best method I found to weld plastic pieces like this is to heat the two faces of the tabs or overlapping pieces until they are soft, and then press them together and let them cool. The plastic will fuse, creating a single piece. It is a little tricky to heat the plastic just enough, but not too much. If you heat it too much it will simply melt and fall apart. The main thing is to try it on a number of test pieces first, and practice.

The best method I found to weld plastic pieces like this is to heat the two faces of the tabs or overlapping pieces until they are soft, and then press them together and let them cool. The plastic will fuse, creating a single piece. It is a little tricky to heat the plastic just enough, but not too much. If you heat it too much it will simply melt and fall apart. The main thing is to try it on a number of test pieces first, and practice. There are many times when the tool you have available does not quite fit the task, and you need to adapt it. This was the case in using the basic heat gun to weld plastic tabs. The provided nozzle of the heat gun produced a fairly broad current of hot air, melting around a larger area than I wanted for welding the plastic tabs together.

There are many times when the tool you have available does not quite fit the task, and you need to adapt it. This was the case in using the basic heat gun to weld plastic tabs. The provided nozzle of the heat gun produced a fairly broad current of hot air, melting around a larger area than I wanted for welding the plastic tabs together. I created a funnel for the heat gun, which focused the hot air down a narrow 3/8″ tube. This produced excellent results in focusing the heat for welding. It also produced a significant side-effect: it choked the air output, so the inside of the heat gun overheated and melted in part. Result: destroyed tool. Good thing it wasn’t expensive.

I created a funnel for the heat gun, which focused the hot air down a narrow 3/8″ tube. This produced excellent results in focusing the heat for welding. It also produced a significant side-effect: it choked the air output, so the inside of the heat gun overheated and melted in part. Result: destroyed tool. Good thing it wasn’t expensive. In my revised design for my replacement heat gun, I used a piece of aluminum curtain rod, with a cross-section shaped like the letter “C”. By having a slit down the side, much of the heat goes to the tip, but the full airflow can still pass out of the heat gun nozzle so the inside of the gun does not overheat. This did not provide as narrow a focus as the original nozzle, but it should at least save the tool from destruction. I made up for it by simply holding another piece of sheet metal in front of areas I did not want to heat.

In my revised design for my replacement heat gun, I used a piece of aluminum curtain rod, with a cross-section shaped like the letter “C”. By having a slit down the side, much of the heat goes to the tip, but the full airflow can still pass out of the heat gun nozzle so the inside of the gun does not overheat. This did not provide as narrow a focus as the original nozzle, but it should at least save the tool from destruction. I made up for it by simply holding another piece of sheet metal in front of areas I did not want to heat. One other approach I tried was spot-welding the tabs together, but I did not come up with a satisfactory technique. The heat gun is too broad to use for this, so I tried a soldering gun instead. You cannot simply stick the tip of the soldering gun into the plastic and melt it, because the plastic will burn and/or make a stringy mess when you pull the soldering gun out. Like the heat gun method, you need a piece of metal to cool with the plastic, which can be removed after a minute.

One other approach I tried was spot-welding the tabs together, but I did not come up with a satisfactory technique. The heat gun is too broad to use for this, so I tried a soldering gun instead. You cannot simply stick the tip of the soldering gun into the plastic and melt it, because the plastic will burn and/or make a stringy mess when you pull the soldering gun out. Like the heat gun method, you need a piece of metal to cool with the plastic, which can be removed after a minute.

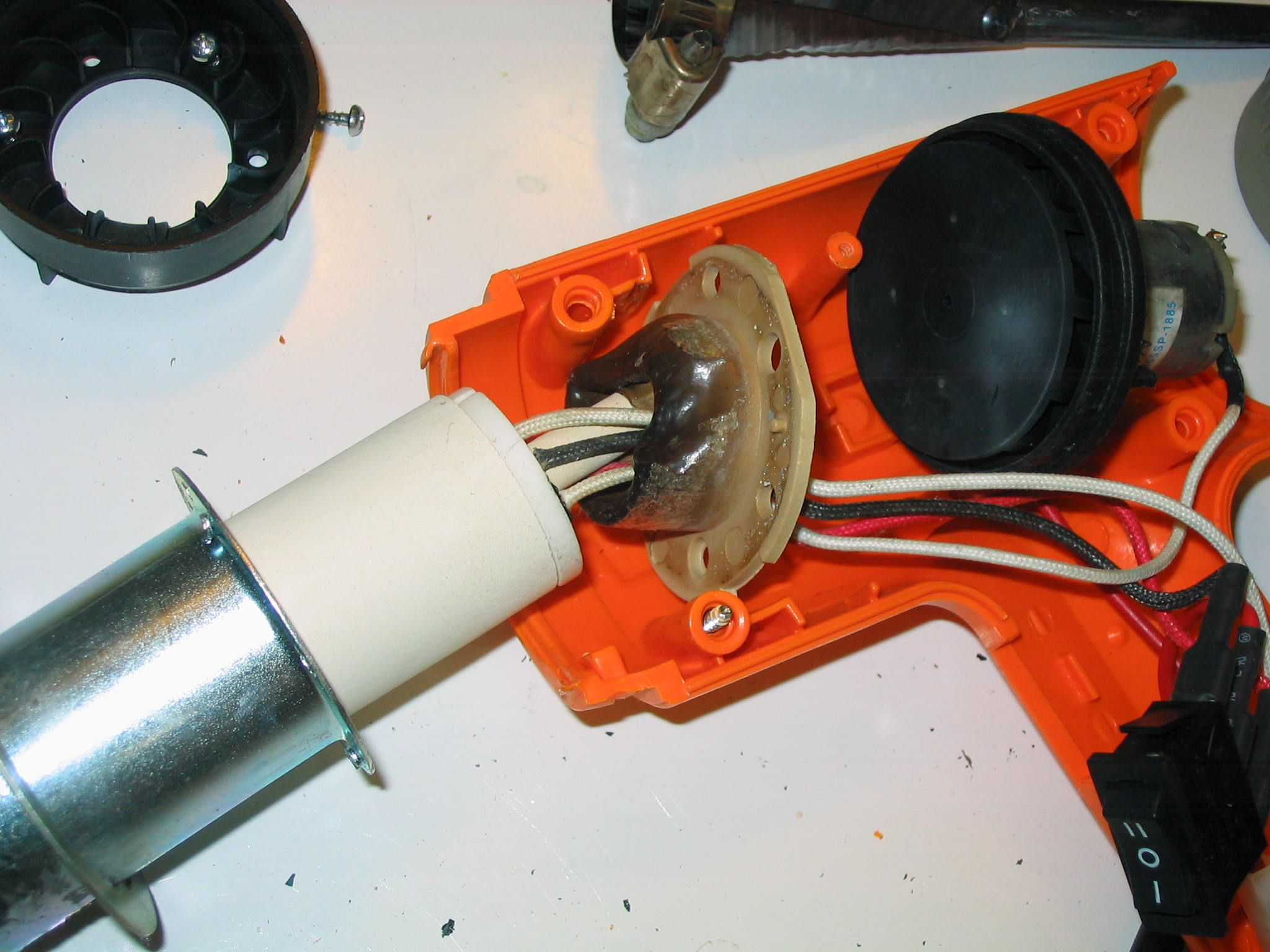

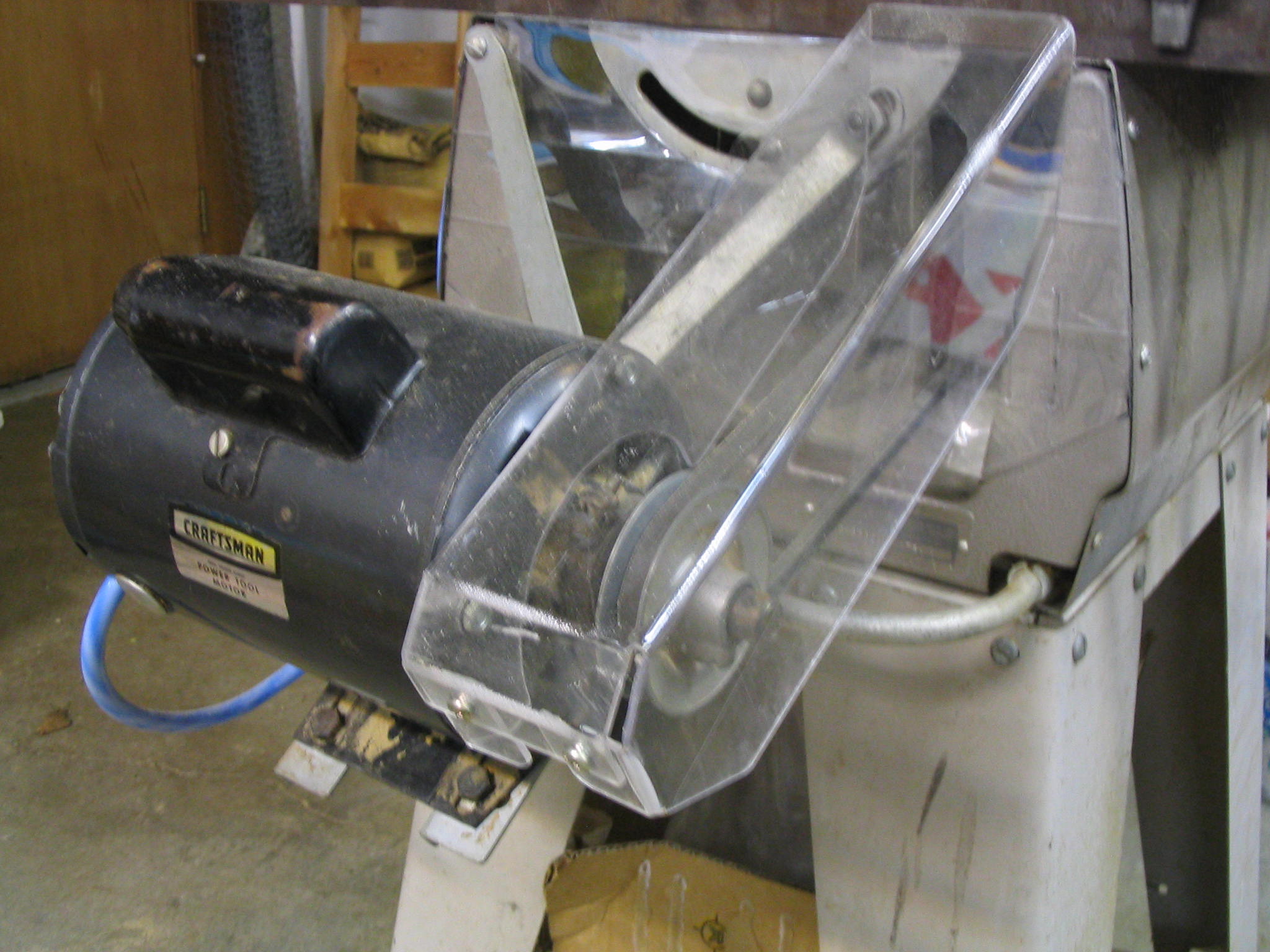

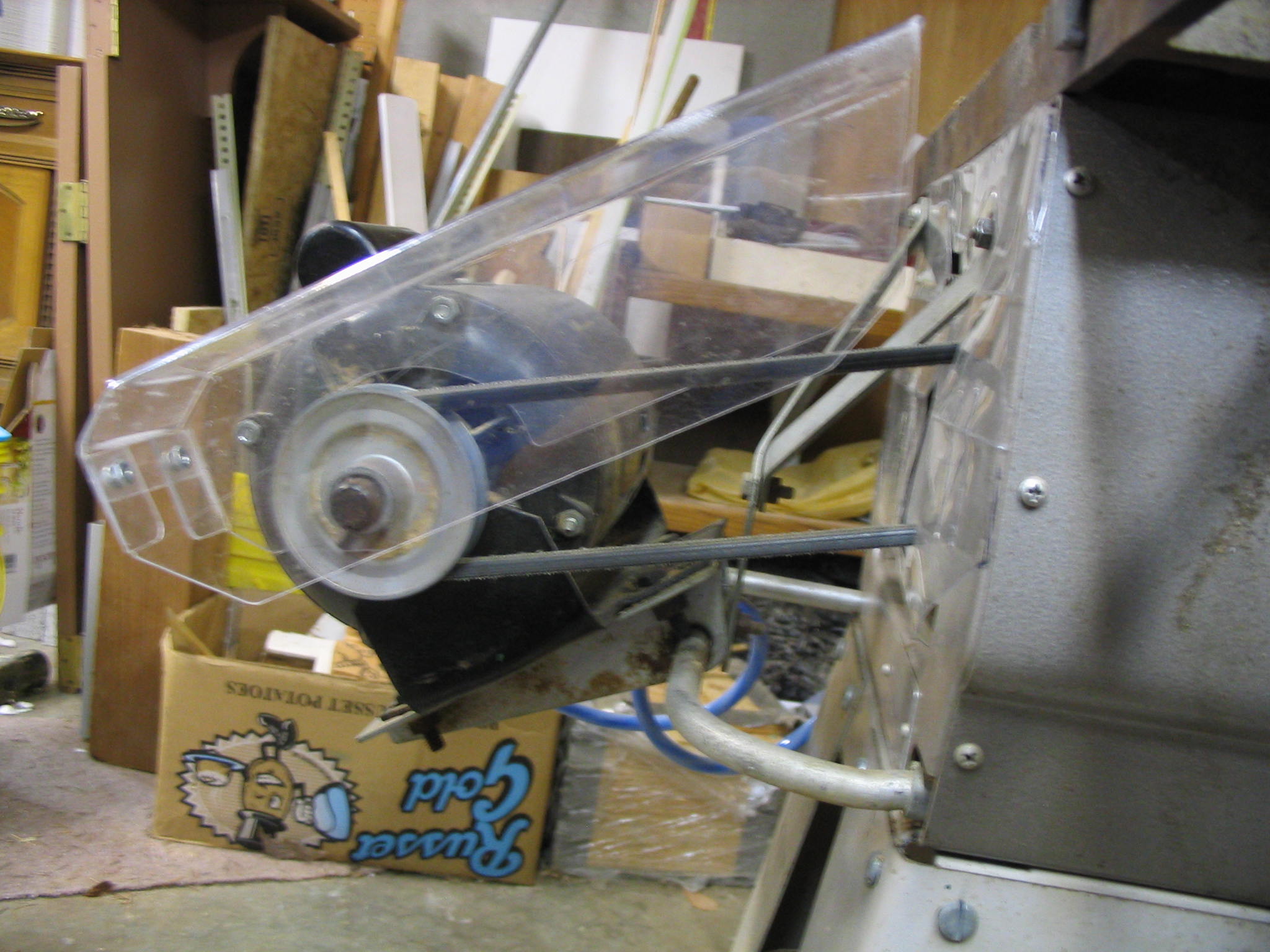

After I repaired the electrical wiring on my garage-sale table saw, I inspected the mechanical workings. It appeared to be in good working condition. There were, however, no modern safety controls. I later found that this table saw was made somewhere around 1956, when blade guards were optional and belt guards weren’t even offered.

After I repaired the electrical wiring on my garage-sale table saw, I inspected the mechanical workings. It appeared to be in good working condition. There were, however, no modern safety controls. I later found that this table saw was made somewhere around 1956, when blade guards were optional and belt guards weren’t even offered.

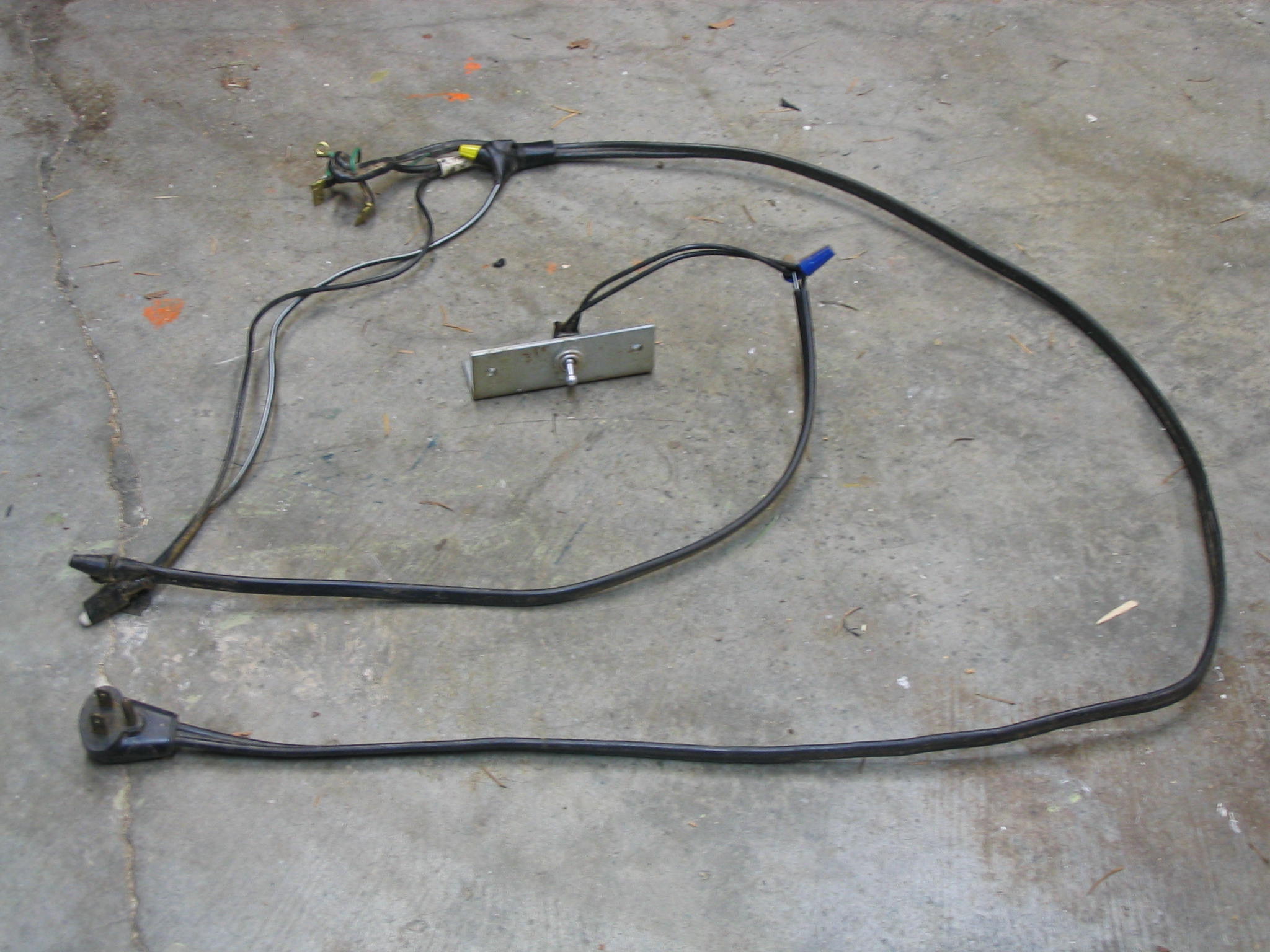

My used tablesaw needed a new power cord and switch. The cord was clearly in bad shape. The on-off switch was spliced in with a mess of wire nuts and electrical tape. It was time for some basic electrical repair.

My used tablesaw needed a new power cord and switch. The cord was clearly in bad shape. The on-off switch was spliced in with a mess of wire nuts and electrical tape. It was time for some basic electrical repair.